Friday, July 31, 2015

Thursday, July 30, 2015

Wednesday, July 29, 2015

Tuesday, July 28, 2015

Monday, July 27, 2015

Sunday, July 26, 2015

Iliad, Book XV - Alexander Pope translation

| And to blue Neptune thus the Goddess calls: | 195 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Attend the mandate of the Sire above, | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| In me behold the Messenger of Jove: | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| He bids thee from forbidden wars repair | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| To thy own deeps, or to the fields of air. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| This if refused, he bids thee timely weigh | 200 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| His elder birthright, and superior sway. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| How shall thy rashness stand the dire alarms, | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| If Heav’n’s omnipotence descend in arms? | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Strivest thou with him, by whom all power is giv’n? | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| And art thou equal to the lord of Heav’n?’ | 205 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘What means the haughty Sov’reign of the Skies?’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| (The King of Ocean thus, incens’d, replies): | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Rule as he will his portion’d realms on high, | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| No vassal God, nor of his train, am I. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Three brother deities from Saturn came, | 210 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| And ancient Rhea, earth’s immortal dame: | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Assign’d by lot, our triple rule we know: | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Infernal Pluto sways the shades below; | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| O’er the wide clouds, and o’er the starry plain, | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ethereal Jove extends his high domain; | 215 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| My court beneath the hoary waves I keep, | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| And hush the roarings of the sacred deep: | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Olympus, and this earth, in common lie; | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| What claim has here the Tyrant of the Sky? | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Far in the distant clouds let him control, | 220 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| And awe the younger brothers of the pole; | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| There to his children his commands be giv’n, | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| The trembling, servile, second race of Heav’n.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘And must I then’ (said she), ‘O Sire of floods! | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bear this fierce answer to the King of Gods? | 225 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Correct it yet, and change thy rash intent; | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| A noble mind disdains not to repent. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| To elder brothers guardian fiends are giv’n, | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| To scourge the wretch insulting them and Heav’n.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Great is the profit’ (thus the God rejoin’d), | 230 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘When ministers are bless’d with prudent mind: | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Warn’d by thy words, to powerful Jove I yield, | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| And quit, tho’ angry, the contended field. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Not but his threats with justice I disclaim, | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| The same our honours, and our birth the same. | 235 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| If yet, forgetful of his promise giv’n | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| To Hermes, Pallas, and the queen of Heav’n, | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| To favour Ilion, that perfidious place, | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| He breaks his faith with half th’ ethereal race; | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Give him to know, unless the Grecian train | 240 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Lay yon proud structures level with the plain, | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Howe’er th’ offence by other Gods be pass’d, | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| The wrath of Neptune shall for ever last.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thus speaking, furious from the field he strode, | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| And plunged into the bosom of the flood. | 245 |

Saturday, July 25, 2015

2:19 -- John Hammond (2001)

| Grand Central Station |

I lost everything I had in the '29 flood

The barn was buried 'neath a mile of mud

Now I've got nothing but the whistle and the steam

My baby's leaving town on the 2:19

I said, hey, hey, I don't know what to do

I will remember you

Hey, hey, I don't know what to do

My baby's leaving town on the 2:19

Now there's a fellow that's preaching 'bout hell and damnation

Bouncing off the walls of the Grand Central Station

I treated her bad, I treated her mean

Baby's leaving town on the 2:19

I said, hey, hey, I will remember you

Hey, hey, I don't know what to do

Hey, I don't know what to do

My baby's leaving town on the 2:19

Now I've always been puzzled by the yin and the yang

It'll come out in the wash, but it always leaves a stain

Sturm and Drang(1), the luster and the sheen

My baby's leaving town on the -

Hey, hey, I don't know what to do

Hey, hey, I will remember you

Hey, hey, I will remember you

My baby's leaving town on the 2:19

Lost the baby with the water(2), and the preacher stole the bride

Sent her out for a bottle, but when she came back inside

She didn't have my whiskey, didn't have my gin(3)

With a hat full of feathers and a wicked grin(4)

I said, hey, hey, I will remember you

Yeah baby, I will remember you

My baby's leaving town on the 2:19

On the train you get smaller, as you get farther away

The roar covers everything you wanted to say

Was that a raindrop or a tear in your eye?

Were you drying your nails or waving goodbye?

Hey, hey, I will remember you

Hey, hey, I don't know what to do

Oh baby

My baby's leaving town on the 2:19

I will remember you

I don't know what to do, baby

Written and produced by: Tom Waits and Kathleen Waits-Brennan

Published by: Jalma Music (ASCAP), © 2001

Official release: Wicked Grin, John Hammond. 2001. Emd/Virgin

John Hammond: Acoustic Guitar and Vocal. Stephen Hodges: Drums, Larry Taylor: Bass. Augie Meyers: Piano

Assistant producer: Marla Hammond. Executive producer: Michael Nash. Engineered and mixed by Oz Fritz

Recorded at Prairie Sun Recording Studios, Cotati, CA or Alpha & Omega Studios, San Rafael, CA

Transcription by Ulf Berggren. Yahoo Groups Tom Waits Discussionlist. July 2, 2001

Notes:

(1) Sturm und Drang: (literally: "storm and stress") was a Germany literary movement that developed during the latter half of the 18th century. It takes its name from a play by F. M. von Klinger. While the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau were a major stimulus of the movement, it developed more immediately as a reaction against what was seen as an overly rationalist literary tradition. Sturm und Drang was revolutionary in its stress on personal subjectivity and on the unease of man in contemporary society, and it firmly established German authors as cultural leaders in Europe at a time when many considered France to be the center of literary development. The movement was also distinguished by the intensity with which it developed the theme of youthful genius in rebellion against accepted standards and by its enthusiasm for nature. The greatest figure of the movement was Goethe, who wrote its first major drama, Götz von Berlichingen (1773), and its most sensational and representative novel, Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (The Sorrows of Young Werther, 1774). Other writers of importance were Klopstock, J. M. R. Lenz, and Friedrich Müller. The last major figure was Schiller, whose Die Räuber and other early plays were also a prelude to romanticism. (Source: Wikipedia/ studies by R. Pascal (1953, repr. 1967) and M. O. Kirsten (1969))

(2) Lost the baby with the water: variation on "Don't throw the baby out with the bath water" or its parallel proverbial expression "To throw the baby out with the bath water" meaning: to reject the good with the bad. (Thanks to Leroy Larson for pointing out this reference. October, 2005)

(3) She didn't have my whiskey, didn't have my gin: "She didn't have my whiskey, didn't have my gin" is very similar to the line "Send out for whiskey, baby, send out for gin" in the Jackson C. Frank song "The Blues Run The Game". Jackson Carey Frank was a relatively unknown folk musician whose life was wrought with depression and medical problems. Although he only released one album, his music has influenced a large number of contemporary folk musicians. Jackson C. Frank died on March 3, 1999. Lyrics (December, 1965): "Catch a boat to England baby maybe to spain. wherever i have gone wherever i have gone. wherever i've been and gone the blues run the game. send out for whiskey baby send out for gin. me and room service oh we're living the life of sin me and room service honey. When i ain't drinking baby you are on my mind me and room service babe when i ain't sleeping honey, when i aint sleeping mama. when i aint sleepin oh you know you'll find me crying. Catch a boat to England baby maybe to Spain. wherever i've been and gone wherever i have gone wherever i have gone the blues run the game. livin is a gamble, baby lovins much the same wherever i have played wherever i throw those dice wherever i have played the blues run the game. maybe when i'm older, baby someplace down the line i'll wake up older so much older mama i'll wake up older and i'll just stop all my tryin. Catch a boat to England baby wherever i have gone wherever i've been and gone maybe to Spain wherever i have gone the blues, they're all the same." (Thanks to Leroy Larson for pointing out this reference. October, 2005)

(4) A wicked grin: Being the title of the 2001 John Hammond album

Friday, July 24, 2015

Is the Chattanooga shooter just another American mass murderer?

| It's worth considering that we are observing in the Chattanooga shooter the same downward spiral that we see in other mass murderers, whether they shoot people in a college lecture hall, or bomb a federal building. Cultural/political factors play a role, but may not be central here. What we have is a young, alienated male, resentful that his life hasn't turned out the way he felt it should, depressed and desirous of self-annihilation, fascinated with firearms, and hoping (delusionally) to make his death more meaningful than his life had been. |

Daily Beast

"His family says Muhammad Youssef Abdulazeez suffered from depression and fought a drug problem and was let go from his job and was having money difficulties and harbored suicidal thoughts.

All of which could explain why the 24-year-old might do something suicidal.

But it does not explain why he would deliberately target an armed forces recruiting center and then a Navy facility, killing four Marines and a sailor.

The reason for that is almost certainly to be found in the pair of blog posts he posted on July 13, the same date his family says he began “a three-day downward spiral” as a result of his personal problems.

In the posts, Abdulazeez describes the material world as a prison and says liberation comes only in following the example set by the disciples of the Prophet Muhammad. He notes that “every one of them fought Jihad for the sake of Allah.”

“We ask Allah to be pleased with us, reward us with Janna,” he writes at the end of the second post, “Janna” being Paradise.

Here he proves himself to be just another dupe who embraced what Islamic extremists offer as an instant solution to all your problems and disappointments.

“If he’s not a terrorist, they ought to redefine the word terrorist,” a counter-terror law enforcement official said Monday.

Most likely, Abdulazeez’s problems go back to the troubled relationship between his parents, which include allegations the mother made in court papers that she had suffered physical and sexual abuse at the hands of the father.

And surely everybody would have been better off if the family had succeeded in getting Abdulazeez into a drug rehab program, as it seems they had hoped to do.

That makes him no less a jihadi than Dylann Roof’s fractured family and drug use made him any less a white supremacist with fantasies of starting a civil war by massacring a Bible study group in a historic black church in Charleston

Extreme, violent ideologies bent on the murder of innocents are seldom havens for the well-adjusted."

Thursday, July 23, 2015

Some cool scientific detective work in that New Yorker earthquake article

| Seattle and/or Portland in the near future? |

New Yorker

"In the late nineteen-eighties, Brian Atwater, a geologist with the United States Geological Survey, and a graduate student named David Yamaguchi found the answer, and another major clue in the Cascadia puzzle. Their discovery is best illustrated in a place called the ghost forest, a grove of western red cedars on the banks of the Copalis River, near the Washington coast. When I paddled out to it last summer, with Atwater and Yamaguchi, it was easy to see how it got its name. The cedars are spread out across a low salt marsh on a wide northern bend in the river, long dead but still standing. Leafless, branchless, barkless, they are reduced to their trunks and worn to a smooth silver-gray, as if they had always carried their own tombstones inside them.

What killed the trees in the ghost forest was saltwater. It had long been assumed that they died slowly, as the sea level around them gradually rose and submerged their roots. But, by 1987, Atwater, who had found in soil layers evidence of sudden land subsidence along the Washington coast, suspected that that was backward—that the trees had died quickly when the ground beneath them plummeted. To find out, he teamed up with Yamaguchi, a specialist in dendrochronology, the study of growth-ring patterns in trees. Yamaguchi took samples of the cedars and found that they had died simultaneously: in tree after tree, the final rings dated to the summer of 1699. Since trees do not grow in the winter, he and Atwater concluded that sometime between August of 1699 and May of 1700 an earthquake had caused the land to drop and killed the cedars. That time frame predated by more than a hundred years the written history of the Pacific Northwest—and so, by rights, the detective story should have ended there.

But it did not. If you travel five thousand miles due west from the ghost forest, you reach the northeast coast of Japan. As the events of 2011 made clear, that coast is vulnerable to tsunamis, and the Japanese have kept track of them since at least 599 A.D. In that fourteen-hundred-year history, one incident has long stood out for its strangeness. On the eighth day of the twelfth month of the twelfth year of the Genroku era, a six-hundred-mile-long wave struck the coast, levelling homes, breaching a castle moat, and causing an accident at sea. The Japanese understood that tsunamis were the result of earthquakes, yet no one felt the ground shake before the Genroku event. The wave had no discernible origin. When scientists began studying it, they called it an orphan tsunami.

Finally, in a 1996 article in Nature, a seismologist named Kenji Satake and three colleagues, drawing on the work of Atwater and Yamaguchi, matched that orphan to its parent—and thereby filled in the blanks in the Cascadia story with uncanny specificity. At approximately nine o’ clock at night on January 26, 1700, a magnitude-9.0 earthquake struck the Pacific Northwest, causing sudden land subsidence, drowning coastal forests, and, out in the ocean, lifting up a wave half the length of a continent. It took roughly fifteen minutes for the Eastern half of that wave to strike the Northwest coast. It took ten hours for the other half to cross the ocean. It reached Japan on January 27, 1700: by the local calendar, the eighth day of the twelfth month of the twelfth year of Genroku.

Once scientists had reconstructed the 1700 earthquake, certain previously overlooked accounts also came to seem like clues. In 1964, Chief Louis Nookmis, of the Huu-ay-aht First Nation, in British Columbia, told a story, passed down through seven generations, about the eradication of Vancouver Island’s Pachena Bay people. “I think it was at nighttime that the land shook,” Nookmis recalled. According to another tribal history, “They sank at once, were all drowned; not one survived.” A hundred years earlier, Billy Balch, a leader of the Makah tribe, recounted a similar story. Before his own time, he said, all the water had receded from Washington State’s Neah Bay, then suddenly poured back in, inundating the entire region. Those who survived later found canoes hanging from the trees. In a 2005 study, Ruth Ludwin, then a seismologist at the University of Washington, together with nine colleagues, collected and analyzed Native American reports of earthquakes and saltwater floods. Some of those reports contained enough information to estimate a date range for the events they described. On average, the midpoint of that range was 1701.

It does not speak well of European-Americans that such stories counted as evidence for a proposition only after that proposition had been proved. Still, the reconstruction of the Cascadia earthquake of 1700 is one of those rare natural puzzles whose pieces fit together as tectonic plates do not: perfectly. It is wonderful science. It was wonderful for science. And it was terrible news for the millions of inhabitants of the Pacific Northwest. As Goldfinger put it, “In the late eighties and early nineties, the paradigm shifted to ‘uh-oh.’ ”

Goldfinger told me this in his lab at Oregon State, a low prefab building that a passing English major might reasonably mistake for the maintenance department. Inside the lab is a walk-in freezer. Inside the freezer are floor-to-ceiling racks filled with cryptically labelled tubes, four inches in diameter and five feet long. Each tube contains a core sample of the seafloor. Each sample contains the history, written in seafloorese, of the past ten thousand years. During subduction-zone earthquakes, torrents of land rush off the continental slope, leaving a permanent deposit on the bottom of the ocean. By counting the number and the size of deposits in each sample, then comparing their extent and consistency along the length of the Cascadia subduction zone, Goldfinger and his colleagues were able to determine how much of the zone has ruptured, how often, and how drastically.

Thanks to that work, we now know that the Pacific Northwest has experienced forty-one subduction-zone earthquakes in the past ten thousand years. If you divide ten thousand by forty-one, you get two hundred and forty-three, which is Cascadia’s recurrence interval: the average amount of time that elapses between earthquakes. That timespan is dangerous both because it is too long—long enough for us to unwittingly build an entire civilization on top of our continent’s worst fault line—and because it is not long enough. Counting from the earthquake of 1700, we are now three hundred and fifteen years into a two-hundred-and-forty-three-year cycle."

Wednesday, July 22, 2015

Child suicide in China: The left behind children

|

| "Because we are too menny." |

WP

"The mother was the first to leave. Perhaps it was domestic abuse that drove her away. Or perhaps it was simply the hopelessness in Cizhu, a village in Guizhou, one of China’s poorest provinces.

One way or another, Ren Xifen abandoned home in 2013. Her husband, Zhang Fangqi, walked out shortly afterward to find work.

They left behind more than a broken marriage, however. Cooped up inside the dusty house were four children, ages 5 to 13. Without their parents, the four siblings would have to fend for themselves.

They didn’t last long.

For two years, the boy and his three younger sisters survived on little more than corn flour, according to one Chinese newspaper. Abandoned by their parents, the children’s personalities changed. They shut themselves inside the cluttered house and refused to open the door even to visiting relatives, the New York Times reported. About a month ago, the kids stopped going to school.

When the doors finally did open on Tuesday, tragedy came tumbling out.

At about 11 p.m., a passerby found the oldest child sprawled out in front of the family’s house, suffering convulsions, according to Agence France-Presse. Neighbors soon found the other three siblings in similar conditions nearby. All four eventually died.

The four children drank pesticide in an apparent suicide pact, Chinese state media reported.

“Thanks for your kindness. I know you mean well for us, but we should go now,” read a note left inside the home, according to the Guardian, citing Xinhua, China’s official news agency.

...

The horrific child suicides have provoked criticism of the absent parents.

...

Popular outrage has been checked, however, by how widespread the practice is in China of parents leaving their children at home while working in distant cities.

China has about 250 million migrant workers, most of whom are drawn from rural villages like Cizhu to mega cities where they can find manufacturing jobs, William Wan wrote in The Washington Post in 2013. Strict government rules and a shortage of schools in big cities mean that many parents leave their kids with grandparents or on their own.

There are roughly 61 million of these “left-behind children,” according to a 2010 China census. More than a third of all kids in rural China live without their parents. Nationwide, nearly 22 percent of Chinese kids have been left behind."

Tuesday, July 21, 2015

Excerpt from an interview with Stonewall Jackson biographer, S.C. Gwynne

"Shortly after Jackson’s death at Chancellorsville, his topographer Jedediah Hotchkiss said, “nearly all regarded [Jackson’s death] as the beginning of the end.” Just how critical was Jackson to the cause of the Confederacy, both tactically and symbolically?

SCG: With his brilliant, underdog victories, Jackson had given the South a myth of invincibility, a sense that, though it had vastly inferior resources and manpower, it could still find a way to win the war. Jackson and Lee embodied this ideal. Jackson’s brilliant tactical maneuvers at battles like Second Manassas and Chancellorsville seemed ultimate proof that one rebel soldier was worth two Yankees.

The legacy of Stonewall Jackson is rich in battlefield glory, as he was already a distinguished combat veteran of the Mexican War before the start of the Civil War. Yet he is also remembered for his deep Christian spirituality and his tremendous sensitivity toward his sister, wife and young daughter. And, of course, no remembrance of Jackson is complete without mention of the personal eccentricities that helped earn him the nickname ‘Tom Fool’ during his years as a professor of natural science at Virginia Military Institute (VMI). How do you think 21st-century Americans should remember Stonewall Jackson?

SCG: Jackson was a brilliant warrior and a deeply complex man. Before the war he was pro-Union and actively tried to organize a national day of prayer to stop the war. Once the war started, he advocated marching north, burning Baltimore, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, and living off the land so that the North would feel the pain of the war. He was a kind and benevolent, though stern, slaveowner and had a complex relationship with the peculiar institution, as many southerners did. He owned 6 slaves. Three came to him through his marriage. One of those, Hetty, raised his wife Anna from birth and was like a surrogate mother; Hetty’s two rowdy sons drove the family carriage. Jackson himself purchased three slaves: one was a man named Albert who came to him and begged Jackson to buy him so he could then be allowed to buy his freedom; another was 4 year old girl with learning disabilities whom Jackson bought after an elderly woman who could no longer care for the girl begged him to buy her; the last, Amy, was about to be sold off to pay debt and also begged Jackson to buy her to deliver her from “her troubles.”

Regarding the latter, a neighbor of Jackson’s wrote to him, “The cup of cold water you have administered to this poor disciple may avail more in the Master’s eye than all the brilliant deed with which you may glorify your country’s battlefields.” When Albert and Amy got sick, he took them in and cared for them. More significantly, Jackson founded, financed and ran a Sunday school for slaves, in direct contravention of Virginia law, which stipulated that slaves could not be taught to read. Jackson, who was accosted several times in the street by citizens who told him he could not get away with it, taught his students to read the Bible anyway. In 1906, an African American minister at the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church in Roanoke, Virginia, an African American church, erected a stained glass window memorializing Jackson’s “colored Sabbath school,” where his parents had both learned to read and been converted to Christianity. The window is there to this day."

Monday, July 20, 2015

Why are so many terrorists engineers?

Mohammad Abdulazeez, 24, who killed four Marines in Chattanooga, TN on July 16, 2015, reportedly graduated from the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in 2012 with a degree in engineering. |

Foreign Policy

"Whiling away his days in a CIA prison in Romania, 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed had a simple request for his captors: Would they allow the mechanical engineer to design a vacuum cleaner?

According to a fascinating Associated Press account of Mohammed’s detainment published on Thursday, the CIA allowed him to do just that, granting the terrorist access to vacuum schematics available online, which he used to re-engineer the appliance.

Mohammed, who faced brutal interrogation practices, was granted the request because the CIA wanted to prevent him from going insane. But Mohammed’s desire to put his engineering acumen to use also raises a question that has long enticed scholars of terrorism: Why is it that so many terrorists have engineering backgrounds?

It’s a question that’s particularly relevant when it comes to Islamic terrorism. Mohammed Atta, the 9/11 hijacker, was an architectural engineer. Two of the three founders of Lashkar e-Taiba, the Pakistani terrorist group, were professors at the University of Engineering and Technology at Lahore. Hezbollah, the Lebanese terrorist group, is chock full of engineers. Jihad al-Binaa, one of its branches, had more than 2,000 engineers working on reconstruction in Lebanon following the 2006 war with Israel.

But the link isn’t just anecdotal. In a 2009 paper, Diego Gambetta, an Oxford sociologist, and Steffen Hertog, a political scientist at the London School of Economics, found that "among violent Islamists with a degree, individuals with an engineering education are three to four times more frequent than we would expect given the share of engineers among university students in Islamic countries." Of a group of 404 members of violent Islamist groups in the Muslim world, Gambetta and Hertog tracked down the course of study for 178 individuals. Of those 178 violent Islamists, 78 (44 percent) were engineers. Broadening the course of study to engineering, medicine, and science, 56.7 percent of their sample had studied these fields.

According to Gambetta and Hertog’s findings, this is a problem unique to violent Islamist groups in the Muslim world. Among nonviolent Islamist groups, for example, engineers are present — but to a far lesser degree than in violent groups. And among violent Islamist groups in the West, education levels tend to be much lower on the whole. Meanwhile, non-Muslim left-wing groups — Germany’s Red Army Faction, Italy’s Red Brigades, and Latin American guerrilla groups — include almost no engineers. Among anarchist groups, engineers are equally absent. Right-wing groups include some engineers, but they are far from overrepresented.

To account for this disparity in occupation among Islamic terrorists in the Muslim world, Gambetta and Hertog sketch out a particular engineering "mindset" in which the profession is "more attractive to individuals seeking cognitive ‘closure’ and clear-cut answers as opposed to more open-ended sciences — a disposition which has been empirically linked to conservative political attitudes." Engineers, the authors find, are far more conservative on the whole than members of other professions. Islamic extremism "rejects Western pluralism and argues for a unified ordered society" — a political worldview that lines up nicely with a profession averse to chaos.

There’s also a societal component. In countries like Egypt, the period after the 1970s was one of massively thwarted expectations, with engineers emerging on the job market only to struggle to find employment. Per the classic explanation of the onset of rebellion — thwarted expectations coupled with relative deprivation — a generation of highly trained students had been made promises (and made subsequent investments in their education) that their societies could not deliver on. Angry, they turned to violence to restore order in society."

Sunday, July 19, 2015

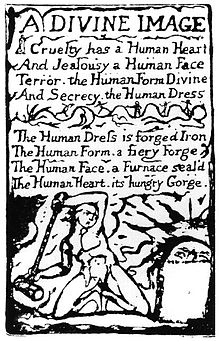

A Divine Image -- William Blake

Cruelty has a Human Heart

And Jealousy a Human Face

Terror the Human Form Divine

And Secrecy, the Human Dress

The Human Dress, is forged Iron

The Human Form, a fiery Forge.

The Human Face, a Furnace seal'd

The Human Heart, its hungry Gorge.

Saturday, July 18, 2015

Don't Think Twice, It's Alright -- Odetta (1965)

It ain’t no use to sit and wonder why, babe

It don’t matter, anyhow

An’ it ain’t no use to sit and wonder why, babe

If you don’t know by now

When your rooster crows at the break of dawn

Look out your window and I’ll be gone

You’re the reason I’m trav’lin’ on

Don’t think twice, it’s all right

It ain’t no use in turnin’ on your light, babe

That light I never knowed

An’ it ain’t no use in turnin’ on your light, babe

I’m on the dark side of the road

Still I wish there was somethin’ you would do or say

To try and make me change my mind and stay

We never did too much talkin’ anyway

So don’t think twice, it’s all right

It ain’t no use in callin’ out my name, gal

Like you never did before

It ain’t no use in callin’ out my name, gal

I can’t hear you anymore

I’m a-thinkin’ and a-wond’rin’ all the way down the road

I once loved a woman, a child I’m told

I give her my heart but she wanted my soul

But don’t think twice, it’s all right

I’m walkin’ down that long, lonesome road, babe

Where I’m bound, I can’t tell

But goodbye’s too good a word, gal

So I’ll just say fare thee well

I ain’t sayin’ you treated me unkind

You could have done better but I don’t mind

You just kinda wasted my precious time

But don’t think twice, it’s all right

Friday, July 17, 2015

False Memory among Hammer Attack Witnesses

| A police officer shot David Baril on May 13, 2015 at Eighth Avenue and 37th Street as Mr. Baril began swinging a hammer at another officer. Witnesses recalled seeing things that did not happen. |

NYT

"The real world of our memory is made of bits of true facts, surrounded by holes that we Spackle over with guesses and beliefs and crowd-sourced rumors. On the dot of 10 on Wednesday morning, Anthony O’Grady, 26, stood in front of a Dunkin’ Donuts on Eighth Avenue in Manhattan. He heard a ruckus, some shouts, then saw a police officer chase a man into the street and shoot him down in the middle of the avenue.

Moments later, Mr. O’Grady spoke to a reporter for The New York Times and said the wounded man was in flight when he was shot. “He looked like he was trying to get away from the officers,” Mr. O’Grady said.

Another person on Eighth Avenue then, Sunny Khalsa, 41, had been riding her bicycle when she saw police officers and the man. Shaken by the encounter, she contacted the Times newsroom with a shocking detail.

“I saw a man who was handcuffed being shot,” Ms. Khalsa said. “And I am sorry, maybe I am crazy, but that is what I saw.”

At 3 p.m. on Wednesday, the Police Department released a surveillance videotape that showed that both Mr. O’Grady and Ms. Khalsa were wrong.

Contrary to what Mr. O’Grady said, the man who was shot had not been trying to get away from the officers; he was actually chasing an officer from the sidewalk onto Eighth Avenue, swinging a hammer at her head. Behind both was the officer’s partner, who shot the man, David Baril.

And Ms. Khalsa did not see Mr. Baril being shot while in handcuffs; he is, as the video and still photographs show, freely swinging the hammer, then lying on the ground with his arms at his side. He was handcuffed a few moments later, well after he had been shot.

There is no evidence that the mistaken accounts of either person were malicious or intentionally false. Studies of memories of traumatic events consistently show how common it is for errors to creep into confidently recalled accounts, according to cognitive psychologists.

“It’s pretty normal,” said Deryn Strange, an associate psychology professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “That’s the hard thing to get our heads around. It’s frightening how easy it is to build in a false memory.”

...

A leading researcher in the field of witness memory, Elizabeth Loftus of the University of California, Irvine, said there was ample evidence that people found ways to plug holes in their recollections.

“If someone has gaps in their narrative, they can fill it in with lots of things,” she said. “Often they fill it with their own expectations, and certainly what they may hear from others.”

These are not the knowingly untrue or devious statements of people who are deliberately lying. False memories can be as persuasive as genuine ones, Dr. Loftus said: “When someone expresses it with detail and confidence and emotion, people are going to believe it.”

Said Dr. Strange, “It is surprising to the average person how quickly memories can be distorted.”

That was certainly Ms. Khalsa’s response.

“I feel totally embarrassed,” she said on Thursday, after having seen the video.

She now believes that she saw the initial encounter and then looked away, as she was on her bicycle. In that moment, the man began the attack, which lasted about three seconds until he was shot. “I didn’t see the civilian run or swing a hammer,” she said. “In my mind I assumed he was just standing there passively, and now is on the ground in handcuffs.”

“With all of the accounts in the news of police officers in shootings, I assumed that police were taking advantage of someone who was easily discriminated against,” she added. “Based on what I saw, I assumed the worst. Even though I had looked away.”

Her own certainty was gone, Ms. Khalsa said.

“It makes me think about everything in life,” she said."

Thursday, July 16, 2015

The Neuroscience of Despair -- Michael W. Begun

New Atlantis

"Pharmaceutical companies sold the idea of depression as much as the drugs themselves, promoting the belief that depression stems from a chemical imbalance in the brain, with a marketing apparatus rival in scope to national political campaigns. (By 2000, pharmaceutical companies were spending over $2 billion in direct-to-consumer advertising. By comparison, spending by candidates in the 2000 presidential election totaled a mere $343 million.) This marketing effort played no small part in shaping the public’s understanding of depression.

The sales of antidepressant drugs increased in kind. According to a 2002 article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, “patients treated for depression were 4.8 times more likely to receive an antidepressant in 1997 than in 1987.” And a 2005 article in Health Affairs reported that in a period of merely five years, between 1996 and 2001, overall spending on SSRIs and other new antidepressants rose from $3.4 billion to $7.9 billion. Edward Shorter writes in A History of Psychiatry (1997) that antidepressants became so popular that “patients began to view physicians as mere conduits to fabled new products rather than as counselors capable of using the doctor-patient relationship itself therapeutically.” While this description may overstate things, it seems likely that the growing popularity of antidepressants and other psychoactive drugs began to reshape our conventional notions of mental disorders.

A Deficient Theory

"It is really not known how drugs alleviate the symptoms of mental disorders,” wrote neuroscientist Elliot S. Valenstein in his book Blaming the Brain (1998), “and it should not be assumed that they do so by correcting an endogenous chemical deficiency or excess.” Valenstein was referring to chemical deficiency (or chemical imbalance) theories of depression, which postulate that depression results from low concentrations of certain neurotransmitters in the brain. Valenstein’s words remain true today: every time a new neurobiological theory seems like it might explain depression, evidence comes along to demonstrate the theory’s inadequacies. The last half century of attempts to formulate such a theory can be summed up by Kafka’s remark: “Like a path in autumn: no sooner is it cleared than it is once again littered with fallen leaves.”

The original chemical deficiency theory of depression dates back to 1965, when Harvard psychiatrist Joseph J. Schildkraut hypothesized that low levels of catecholamines — a kind of neurotransmitter, or brain chemical — were associated with depressive disorders, with high levels corresponding to feelings of elation. The paper remains one of the most frequently cited in the history of psychiatry. While the hypothesis may appear rudimentary today, it laid the groundwork for current chemical imbalance theories of depression.

Schildkraut inspired the development of the monoamine hypothesis, which postulates that deficiencies in certain neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine cause depression. (Monoamines are a class of neurotransmitters that includes serotonin, dopamine, and catecholamines, such as norepinephrine.) In contrast to early antidepressant drugs, which were discovered serendipitously, the later SSRIs were designed on the basis of the monoamine hypothesis. They were expressly engineered to increase the amount of serotonin available in synapses, the junctions between neurons. While SSRIs have proven to be more effective than most other antidepressant drugs, we know little about how they work beyond their immediate biochemical effects. One particular problem scientists have tried to understand is that while the physical effects of SSRIs and other antidepressant drugs transpire within minutes after consumption, the psychological effects typically take nearly two weeks to manifest. This difficulty has prompted further hypotheses and speculative modifications to the monoamine theory, but no empirically bulletproof explanation has thus far been found.

Evidence suggests that nothing close to the simple chemical deficiency hypothesis can be right. Despite intense efforts to correlate serotonin deficiencies with depression, most studies have been unable to do so. The same goes for other monoamines, too. Only about 25 percent of depressed patients actually have low levels of serotonin or norepinephrine, according to Valenstein, suggesting that other processes are involved.

These shortcomings have not stopped the chemical imbalance theory from shaping popular discourse about depression and mental illness in general. Advertisements for antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications have frequently appealed to the chemical imbalance hypothesis, sometimes cartoonishly depicting the deficiency in neurotransmitters that was supposed to cause depression. A Prozac advertisement that ran in Newsweek, Time, and other popular magazines around 1997 and 1998 explained:

When you’re clinically depressed, one thing that can happen is the level of serotonin (a chemical in your body) may drop. So you may have trouble sleeping. Feel unusually sad or irritable. Find it hard to concentrate. Lose your appetite. Lack energy. Or have trouble feeling pleasure.... To help bring serotonin levels closer to normal, the medicine doctors now prescribe most often is Prozac.®

The advertisement respects FDA regulations against false drug advertising statements by including the qualification “one thing that can happen,” though it presents a seductive explanation of a whole range of woes we experience on a daily basis. The mismatch between the empirical status of the chemical deficiency hypothesis and its portrayal in pharmaceutical advertisements led a 2005 paper published in PLOS Medicine to conclude: “The incongruence between the scientific literature and the claims made in FDA-regulated SSRI advertisements is remarkable, and possibly unparalleled.” This kind of aggressive advertising on the part of the pharmaceutical companies (among other practices like political lobbying, incentivizing doctors to prescribe their products, and promoting screening for depression) has led many authors to lambast the pharmaceutical industry for selling the idea of depression just as much as its treatment.

The chemical deficiency hypothesis may itself be deficient, but it helped make possible a new subdiscipline, biological psychiatry, in which mental disorders are understood as arising from facts about the biology of the person. Most psychiatrists today point to more complex explanations than those offered by Schildkraut in the 1960s. For instance, in a 2011 letter to the New York Review of Books, two psychiatrists wrote of “recent advances in neuroscience research that demonstrate that depression is not a disease of a single neurotransmitter system or brain region but probably a disorder that involves multiple neural circuits and neurotransmitters.” Schildkraut himself stressed that his chemical imbalance hypothesis was “undoubtedly, at best, a reductionistic oversimplification of a very complex biological state,” and that it was properly regarded as a heuristic rather than a sufficient explanation of the neurobiology of depression. Yet the form of explanation, in which a mental disorder is related to a neuronal abnormality, has not changed since Schildkraut’s hypothesis first took hold, and today we seem ever more committed to neurobiological explanations of mental illness. How far can they go?"

Wednesday, July 15, 2015

The Memoirs of Barry Lyndon, Esq., Chapter Four

"Were these Memoirs not characterised by truth, and did I deign to utter a single word for which my own personal experience did not give me the fullest authority, I might easily make myself the hero of some strange and popular adventures, and, after the fashion of novel-writers, introduce my reader to the great characters of this remarkable time. These persons (I mean the romance-writers), if they take a drummer or a dustman for a hero, somehow manage to bring him in contact with the greatest lords and most notorious personages of the empire; and I warrant me there's not one of them but, in describing the battle of Minden, would manage to bring Prince Ferdinand, and my Lord George Sackville, and my Lord Granby, into presence. It would have been easy for me to have SAID I was present when the orders were brought to Lord George to charge with the cavalry and finish the rout of the Frenchmen, and when he refused to do so, and thereby spoiled the great victory. But the fact is, I was two miles off from the cavalry when his Lordship's fatal hesitation took place, and none of us soldiers of the line knew of what had occurred until we came to talk about the fight over our kettles in the evening, and repose after the labours of a hard-fought day. I saw no one of higher rank that day than my colonel and a couple of orderly officers riding by in the smoke—no one on our side, that is. A poor corporal (as I then had the disgrace of being) is not generally invited into the company of commanders and the great; but, in revenge, I saw, I promise you, some very good company on the FRENCH part, for their regiments of Lorraine and Royal Cravate were charging us all day; and in THAT sort of MELEE high and low are pretty equally received. I hate bragging, but I cannot help saying that I made a very close acquaintance with the colonel of the Cravates; for I drove my bayonet into his body, and finished off a poor little ensign, so young, slender, and small, that a blow from my pigtail would have despatched him, I think, in place of the butt of my musket, with which I clubbed him down. I killed, besides, four more officers and men, and in the poor ensign's pocket found a purse of fourteen louis-d'or, and a silver box of sugar-plums; of which the former present was very agreeable to me. If people would tell their stories of battles in this simple way, I think the cause of truth would not suffer by it. All I know of this famous fight of Minden (except from books) is told here above. The ensign's silver bon-bon box and his purse of gold; the livid face of the poor fellow as he fell; the huzzas of the men of my company as I went out under a smart fire and rifled him; their shouts and curses as we came hand in hand with the Frenchmen,—these are, in truth, not very dignified recollections, and had best be passed over briefly. When my kind friend Fagan was shot, a brother captain, and his very good friend, turned to Lieutenant Rawson and said, 'Fagan's down; Rawson, there's your company.' It was all the epitaph my brave patron got. 'I should have left you a hundred guineas, Redmond,' were his last words to me, 'but for a cursed run of ill luck last night at faro.' And he gave me a faint squeeze of the hand; then, as the word was given to advance, I left him. When we came back to our old ground, which we presently did, he was lying there still; but he was dead. Some of our people had already torn off his epaulets, and, no doubt, had rifled his purse. Such knaves and ruffians do men in war become! It is well for gentlemen to talk of the age of chivalry; but remember the starving brutes whom they lead—men nursed in poverty, entirely ignorant, made to take a pride in deeds of blood—men who can have no amusement but in drunkenness, debauch, and plunder. It is with these shocking instruments that your great warriors and kings have been doing their murderous work in the world; and while, for instance, we are at the present moment admiring the 'Great Frederick,' as we call him, and his philosophy, and his liberality, and his military genius, I, who have served him, and been, as it were, behind the scenes of which that great spectacle is composed, can only look at it with horror. What a number of items of human crime, misery, slavery, go to form that sum-total of glory! I can recollect a certain day about three weeks after the battle of Minden, and a farmhouse in which some of us entered; and how the old woman and her daughters served us, trembling, to wine; and how we got drunk over the wine, and the house was in a flame, presently; and woe betide the wretched fellow afterwards who came home to look for his house and his children!"

Tuesday, July 14, 2015

fMRIs of Aircraft Emergency Passengers don't show much

| So, do an fMRI study of 8 participants and you get publication and press attention. Do intensive psychotherapy with 80 traumatized patients and you get resolution of symptoms in the vast majority of your cases. Who do you think knows more about the effects of traumatic experiences on human beings? The psychotherapist or the neuroscientist? |

"Neuroimaging data collected from a group of passengers who thought they were going to die when their plane ran out of fuel over the Atlantic Ocean in the summer of 2001 are helping psychology researchers better understand trauma memories and how they’re processed in the brain.

A total of eight passengers agreed to undergo fMRI scanning while they looked at video recreation of the Air Transat incident, footage of the 9/11 attacks, and a neutral event. The participants ranged in age from 30s to 60s; while some had a diagnosis of PTSD, most did not.

“This traumatic incident still haunts passengers regardless of whether they have PTSD or not. They remember the event as though it happened yesterday, when in fact it happened almost a decade ago (at the time of the brain scanning). Other more mundane experiences tend to fade with the passage of time, but trauma leaves a lasting memory trace,” said Daniela Palombo, the study’s lead author and currently a post-doctoral researcher at VA Boston Healthcare System and Boston University School of Medicine. “We’ve uncovered some hints into the brain mechanisms through which this may occur.”

The participants’ showed heightened responses in a network of brain regions known to be involved in emotional memory – including the amygdala, hippocampus, and midline frontal and posterior regions — when they recalled their experience on AT Flight 236 compared to when they remembered a neutral autobiographical memory.

The passengers showed a similar pattern of heightened brain activity in relation to the 9/11 terrorist attacks, another significant but less personal trauma that occurred just three weeks after the Air Transat incident. This enhancement effect was not evident in the brains of a comparison group of individuals when they recalled 9/11 during their fMRI scan.

According to Palombo, the “carryover effect” may indicate that the Air Transat flight scare changed the way the passengers process new information, possibly making them more sensitive to other negative life experiences.

“Research on highly traumatic memory relies on animal studies, where brain responses to fear can be experimentally manipulated and observed,” said Brian Levine, senior scientist at Baycrest Health Science’s Rotman Research Institute, Professor of Psychology at the University of Toronto, and senior author on the paper. “Thanks to the passengers who volunteered, we were able to examine the human brain’s response to traumatic memory at a degree of vividness that is generally impossible to attain.”

In the first phase of the study, published in 2014, the research team found that all of the passengers who participated remembered a remarkable amount of detail for the Air Transat incident, regardless of whether or not they had PTSD, although individuals with PTSD tended to veer off topic and recall additional information that was not central to the events assessed."

Palombo, D., McKinnon, M., McIntosh, A., Anderson, A., Todd, R., & Levine, B. (2015). The neural correlates of memory for a life-threatening event: An fMRI study of passengers from Flight AT236 Clinical Psychological Science. DOI: 10.1177/2167702615589308

Monday, July 13, 2015

What is the point of having all those books??

The PointMag

"Delight in book collecting, and in showing off one’s book collection, is common, if not universal, among readers and would-be-readers. The biggest reason we spend money on books is because we want to read them (eventually), but that isn’t the only reason: we also like to look at them, and to look at other people looking at them. While moving into my new apartment this month I found myself casting long, admiring glances at my full bookshelves, straightening out folded pages and making sure the spines were perfectly lined up. I have devoted most of my moving time to arranging these shelves; books accounted for probably 90 percent of the weight I had to lift up three flights of stairs into my apartment. When I move out in two years, I will have to do it all again. Why do I—why do we—devote so much time, energy, space and money to these $15 hunks of paper? Why do I risk compressed discs every time I move into a new apartment? Or, to put it another way: Why don’t I just buy a Kindle?

Because I love books—or so I tell myself. But what exactly am I talking about when I talk about “books”? When I say I love Tao Lin’s Taipei, for example, am I talking about the enriching experience of reading that novel? Or am I talking about my physical copy of Taipei, whose glittery spine looks especially dazzling sandwiched between Primo Levi and David Lipsky? In order to distinguish my hobby of collecting books from, say, my mother’s hobby of collecting ceramic iguanas, I have to claim that it is distinguished by the experience of the reading itself. I have to claim that in collecting and reading all these books I am doing something productive, constructive, worthwhile. This, at least, has been the argument made by the various defenders of literature that have been mounted of late in, to give a far from exhaustive list, Slate, Time, the New York Times, the Atlantic, Popular Science, and the New Republic. These articles have either championed or criticized recent scientific research that supposedly proves that reading literature makes one a more empathetic person. I tend to agree with Leo Robson in feeling that this scientific research is probably bullshit, but even Robson comes around to the idea that reading literature does something positive for the reader, even if that thing may have little to do with morality.

But if all this reading has improved me somehow, you wouldn’t know it from the way I behave around my books. In fact, when I spend hours arranging my bookshelves and buying books I won’t read any time soon, I’m acting like the only thing I want to get out of reading Taipei is the chance to show off its shiny cover on my bookshelf. The way I treat my books shows that no matter how important they are to me as things to read, they also exist as decorative objects and status symbols."

Sunday, July 12, 2015

The Rusty Man -- Herman Melville

(By a timid one)

In La Mancha he mopeth

With beard thin and dusty;

He doteth and mopeth

In library fusty —

'Mong his old folios gropeth:

Cites obsolete saws

Of chivalry's laws —

Be the wronged one's knight:

Die, but do right.

So he rusts and musts,

While each grocer green

Thriveth apace with the fulsome face

Of a fool serene.

Saturday, July 11, 2015

Brother Love's Traveling Salvation Show - Neil Diamond

Hot August night

And the leaves hanging down

And the grass on the ground smellin' sweet

Move up the road to the outside of town

And the sound of that good gospel beat

Sits a ragged tent

Where there ain't no trees

And that gospel group tellin' you and me

It's Love, Brother Love, say

Brother Love's Traveling Salvation Show

Pack up the babies and grab the old ladies

And ev'ryone goes, 'cause everyone knows

Brother Love's show

Room gets suddenly still

And when you'd almost bet

You could hear yourself sweat, he walks in

Eyes black as coal

And when he lifts his face

Ev'ry ear in the place is on him

Starting soft and slow

Like a small earthquake

And when he lets go,

Half the valley shakes

It's Love, Brother Love, say

Brother Love's Traveling Salvation Show

Pack up the babies and grab the old ladies

And ev'ryone goes, 'cause everyone knows

Brother Love's show

[Sermon]

Take my hand in yours,

Walk with me this day

In my heart I know, I will never stray

Halle, halle, halle, halle

Halle, halle, halle, halle

It's Love, Brother Love, say

Brother Love's Traveling Salvation Show

Pack up the babies

And grab the old ladies and ev'ryone goes

I say, Love, Brother Love, say

Brother Love's Traveling Salvation Show

Pack up the babies

And grab the old ladies and ev'ryone goes...

Friday, July 10, 2015

The First Names on the Vietnam Wall

| It's actually 56 years ago, but I couldn't find a better graphic. |

RCP

"Fifty-six years ago...the Viet Cong killed two American soldiers and wounded a third in an ambush at a South Vietnamese army camp in the small town of Bien Hoa about 20 miles northeast of Saigon.

The Viet Cong had been regularly assassinating South Vietnamese officials, but except for a single 1957 incident they had refrained from attacking Americans. The Bien Hoa assault signaled that they were refraining no longer.

Killed that day were Maj. Dale Richard Buis and Master Sgt. Chester M. Ovnand. Two South Vietnamese soldiers were also killed in the raid, along with an 8-year-old boy from the village, and one of the attackers.

Both of the slain Americans were career military men. Born in Pender, Nebraska, in 1921, Maj. Buis had served in World War II and Korea. He’d been at Bien Hoa only two days, and the night he was killed, he was showing his new comrades pictures of his three young sons, who were back home with his wife in Imperial Beach, California. Sgt. Ovnand, 45, had just written a letter to his wife back on Copperas Cove, Texas.

They were among a contingent of eight Americans “advisers” at Bien Hoa: the official name of their unit was U.S. Military Assistance Advisory Group. It was R&R time, and two officers were off playing tennis. Six others remained in the mess hall to watch a murder mystery called “The Tattered Dress.”

It was a two-reel picture, and after the first reel, Sgt. Ovnand turned on the lights and went back to the projector. That’s when all hell broke loose.

* * *

Stanley Karnow, a reporter covering Asia for Time-Life publications, was in Saigon on July 8, 1959, when he heard about the attack on Americans in Bien Hoa. A World War II veteran who would later win a Pulitzer Prize for his comprehensive books about the region, Karnow commandeered a cab to the scene of the ambush. What he discovered after interviewing the survivors would be communicated back to the United States in a dispatch published the following week.

Karnow used the word “terrorists” to describe the attackers, as did the U.S. Army; certainly, the attack was terrifying: Six unarmed Americans stationed abroad take a break from their duties to watch a movie only to be attacked out of the darkness.

Karnow’s report ended this way:

“In the first murderous hail of bullets, Ovnand and Major Buis fell and died within minutes. Captain Howard Boston of Blairsburg, Iowa was seriously wounded, and two Vietnamese guards were killed. Trapped in a crossfire, all six might have died had not Major Jack Hellet of Baton Rouge leaped across the room to turn out the lights -- and had not one of the terrorists who tried to throw a homemade bomb into the room miscalculated and blown himself up instead. Within minutes Vietnamese troops arrived, but the rest of the assassins had already fled.”"

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)