Here's the summary: Researchers find that children whose parents speak to them more when they are little do better in school years later. It also was found that poor people spoke less to their young kids than rich people. So now do-gooders are trying to get poor mothers to talk to their babies more. You can read the entire New York Times blogpost here, or just the excerpts below:

By the time a poor child is 1 year old, she has most likely already fallen behind middle-class children in her ability to talk, understand and learn. The gap between poor children and wealthier ones widens each year, and by high school it has become a chasm. American attempts to close this gap in schools have largely failed, and a consensus is starting to build that these attempts must start long before school — before preschool, perhaps even before birth.

There is no consensus, however, about what form these attempts should take, because there is no consensus about the problem itself. What is it about poverty that limits a child’s ability to learn? Researchers have answered the question in different ways: Is it exposure to lead? Character issues like a lack of self-control or failure to think of future consequences? The effects of high levels of stress hormones? The lack of a culture of reading?

Another idea, however, is creeping into the policy debate: that the key to early learning is talking — specifically, a child’s exposure to language spoken by parents and caretakers from birth to age 3, the more the better. It turns out, evidence is showing, that the much-ridiculed stream of parent-to-child baby talk — Feel Teddy’s nose! It’s so soft! Cars make noise — look, there’s a yellow one! Baby feels hungry? Now Mommy is opening the refrigerator! — is very, very important. (So put those smartphones away!)Intelligence, as measured by IQ scores and as demonstrated by academic and occupational achievement, happens to be highly heritable. How smart your child is and how well he does in school is strongly influenced by how smart his four grandparents were. Adopted children resemble their biological parents in intelligence more than they resemble their adoptive parents who raised them from birth. Socio-economic status and intelligence are positively correlated. All of these facts are diligently ignored by the writer of this article.

The mother who speaks to her infant a lot more than the average parent is probably a lot more intelligent than the average parent. When you observe her, you are not identifying a good parenting technique, you are observing a sign of higher intelligence. Her child is probably already smarter than the average toddler, largely as a result of his genetic inheritance. [By the way, if her kid just stared blankly at her when she spoke (e.g., due to a head injury or autism) she would eventually speak to him much less often.]

Many developmental psychologists ignore the heritability of IQ and concentrate instead on environmental effects, like how much a parent talks to her child. But a person (phenotype) is the product of their genetics (genotype) and their environment. You don't get to ignore any element in that G x E = P equation. People seize upon ideas like, "Talking to your baby more will increase his later school achievement," because they can't bear to says things like, "How well a kid does in school can be predicted by how well his parents did in school."

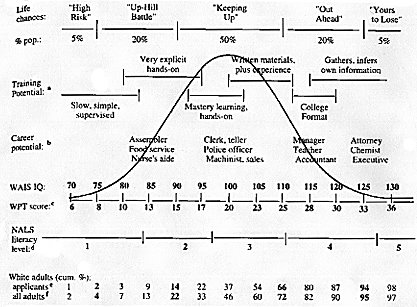

The heritability of IQ is not only substantial but also totally unfair. The unfairness is aggravated because of assortative mating (smart people tend to mate with other smart people). The increasing complexity of modern life makes higher cognitive capacity ever more advantageous. It is becoming harder and harder for people of lower intelligence to get on as the world becomes more cognitively complex. People on the far right tail of the IQ bell curve should thank their lucky stars -- they won a genetic lottery. They should also realize that they are not morally superior to those on the far left tail. Perhaps, Mr. Smartypants, your unearned position entails some serious obligations towards those less fortunate.

Hart and Risley were studying how parents of different socioeconomic backgrounds talked to their babies. Every month, the researchers visited the 42 families in the study and recorded an hour of parent-child interaction. They were looking for things like how much parents praised their children, what they talked about, whether the conversational tone was positive or negative. Then they waited till the children were 9, and examined how they were doing in school....

All parents gave their children directives like “Put away your toy!” or “Don’t eat that!” But interaction was more likely to stop there for parents on welfare, while as a family’s income and educational levels rose, those interactions were more likely to be just the beginning.

The disparity was staggering. Children whose families were on welfare heard about 600 words per hour. Working-class children heard 1,200 words per hour, and children from professional families heard 2,100 words. By age 3, a poor child would have heard 30 million fewer words in his home environment than a child from a professional family. And the disparity mattered: the greater the number of words children heard from their parents or caregivers before they were 3, the higher their IQ and the better they did in school. TV talk not only didn’t help, it was detrimental.

Hart and Risley later wrote that children’s level of language development starts to level off when it matches that of their parents — so a language deficit is passed down through generations. They found that parents talk much more to girls than to boys (perhaps because girls are more sociable, or because it is Mom who does most of the care, and parents talk more to children of their gender). This might explain why young, poor boys have particular trouble in school. And they argued that the disparities in word usage correlated so closely with academic success that kids born to families on welfare do worse than professional-class children entirely because their parents talk to them less. In other words, if everyone talked to their young children the same amount, there would be no racial or socioeconomic gap at all. (Some other researchers say that while word count is extremely important, it can’t be the only factor.)Well, we'll see how well this latest fad works out. So far, they found that they might be able to increase the number of words poor women direct at their infants and toddlers. But that is a long way from demonstrating a positive impact on school achievement. Since nothing else* has ever worked to increase school achievement among the poor, I'm guessing that this will turn out the same way. But, like I said, we'll see.

A few years ago, developmental psychologists noticed that kids whose parents read to them did better in school than kids whose parents didn't read to them. So, they tried to get more parents to read to their kids, and even tried to tell them how to read to their kids (asking questions like, "What do you think is going to happen next?"). Well, that didn't work, because there's a reason why some people don't read to their kids -- because you don't read to your kids if reading is difficult or even painful for you. And this person who can't read is much more likely to have a kid who can't read than a parent who reads for pleasure -- whether or not the parent who reads for pleasure ever reads to her kid.

*Here's an excerpt from a study that claims that Head Start improves cognitive outcomes (compared to children who would otherwise be cared for at home by their single-mothers on welfare):

Our estimates of Head Start effects were roughly comparable to those reported in the Head Start Impact Study. For example, when comparing children who attended Head Start with all other children, we found that the effect sizes for PPVT–III and WJ–R Letter–Word Identification from the propensity score matching models (which essentially were treatment-on-treated [TOT] analyses) were 0.19 and 0.16, respectively; while the effect sizes for social competence and attention problems were 0.14 and −0.16, respectively.Okay. First of all, you made their attention problems worse by sending them to Head Start. But secondly, those effect sizes are puny. If you had a treatment for depression with those kind of effect sizes, by the end of the study you would still have a bunch of depressed patients.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.