The American Scholar

"What was the appeal of English during those now long-ago days? For me, English as a way of understanding the world began at Haverford College, where I was an undergraduate in the late 1950s. The place was small, the classrooms plain, the students all intimidated boys, and the curriculum both straightforward and challenging. What we read forced us to think about the words on the page, their meaning, their ethical and psychological implications, and what we could contrive (in 500-word essays each week) to write about them. With the books in front of us, we were taught the skills of interpretation. Our tasks were difficult, the books (Emerson’s essays, David Copperfield, Shaw’s Major Barbara, the poetry of Emily Dickinson, and a dozen other works) were masterly, and our teacher possessed an authority it would have been “bootless” (his word) to question.

...

Finding pleasure in such reading, and indeed in majoring in English, was a declaration at the time that education was not at all about getting a job or securing one’s future. In comparison with the pre-professional ambitions that dominate the lives of American undergraduates today, the psychological condition of students of the time was defined by self-reflection, innocence, and a casual irresponsibility about what was coming next.

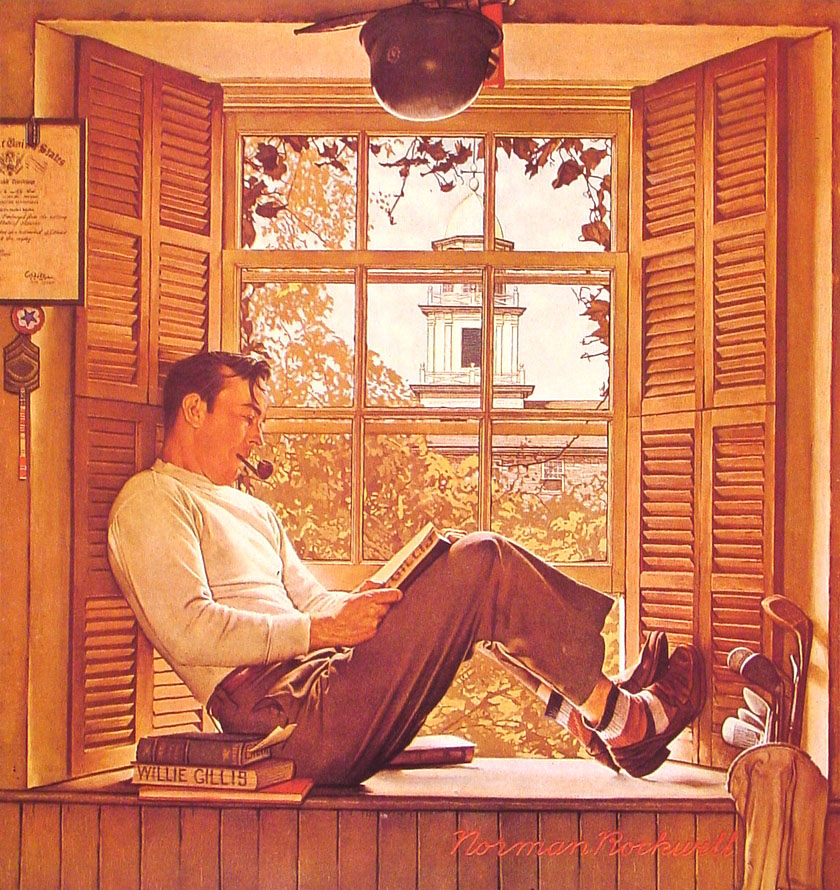

Also visible in the late 1940s and early 1950s were thousands of GIs returning from World War II with a desire to establish for themselves lives as similar as possible to those they imagined had been led by the college generation before their own. For these veterans, college implied security and tradition, a world unlike the one they had left behind in Europe and the Pacific. So they did what they thought one always did in college: study, reflect, and learn. They would reconnect, they thought, with the cultural traditions the war had been fought to defend. Thus a curriculum complete with “great books” and a pantheon of established authors went without question for those students, and it was reinforced for everybody else.

For those like me who immediately followed them in the 1950s and early 1960s, the centrality of the humanities to a liberal education was a settled matter. But by the end of the 1960s, everything was up for grabs and nothing was safe from negative and reductive analysis. Every form of anti-authoritarian energy—concerning sexual mores, race relations, the war in Vietnam, mind-altering drugs—was felt across the nation (I was at Berkeley, the epicenter of all such energies). Against such ferocious intensities, few elements of the cultural patterns of the preceding decades could stand. The long-term consequences of such a spilling-out of the old contents of what college meant reverberate today."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.