I am a big fan of reading lists. You can't encounter a good one without learning of a book that you had never heard of before but end up wanting desperately to read. This recent piece from the Daily Beast seems a like a good place to start if you are looking for something worth reading. I agree strongly with the list contributors who believe that college students should read hundreds of books by the time they graduate.

With regard to yesterday's post, by the way, I also agree that I never would have made it through Joyce's Ulysses unless I was enrolled in a literature course while I was reading it. I would definitely require Shakespeare (especially the tragedies), Tolstoy, Joyce, Pascal, Montaigne, and Dickens. The rest of the suggestions seem a bit idiosyncratic to me, but don't let that stop you.

"There can’t be one book; there must be a library; that has got to be the lesson. But, for a start, to ponder the shape and rhythm and meaning of life: Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man together with Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations.

Mythologies, by Roland Barthes. This little book is valuable not only for Barthes’s lucid writing and rich sense of irony, but also because, more than ever, we need the kind of interpretive skills he demonstrates. All young people, college educated or not, should be able to interpret their society in a skeptical way, and see through the myths of the media-saturated environment.

The one book everyone should read before leaving college is Ulysses by James Joyce. It is without doubt the seminal novel of the 20th century. But Ulysses makes such intense demands on the reader—and requires such a deep engagement with the history of English literature—that if you don’t read it in college as part of a fiction course then the chances are you won’t—and even if you were to, you wouldn’t understand half the allusions.

The Man Who Planted Trees, by Jean Giono. Such a hopeful vision about everybody doing his or her part. It teaches students who are going out into the world how to make the right decisions about what they eat and how they live.

Family Happiness by Leo Tolstoy. War and Peace is asking too much; Family Happiness, a novella published in 1859 that takes about two hours to read, is a bite-sized substitute. It uncannily captures inside a very small frame how it feels to fall in love, and then how it feels to go from being in love to something lesser that still isn’t exactly out of love. As such it makes for an excellent short introduction to the capability and power of literary art, and to the vexedness of being human.

All college students should have to read a couple hundred books before they graduate, but since we’re not funding undergraduates like that (who has money for schools once you’re done giving oil companies their subsidies?) I recommend Toni Morrison’s Beloved, a book that stabs straight at the heart of the American experience. Yes, it’s a novel about slavery, whose nightmare legacy continues to haunt our country as surely as it haunts the novel’s characters. Beloved is also about a woman slaughtering her children rather than having them sent back into slavery. Beloved is also about creating a self after you and your world have nearly been destroyed. No question: Beloved is a tough book but there’s really no understanding the United States without it.

Adventures of Ideas by Alfred North Whitehead. They don’t want to graduate until they read that book. And if they do graduate, read it the next day!

The Image by Daniel J. Boorstin In 1961, before the Vietnam War was close to being televised, Boorstin identified the basic laws and contours of image culture—among them, a longing for authenticity that naturally results from increased mediation of human experience. His observations hold eerily true even in the era of Facebook and YouTube.

Pascal’s Pensees. They’re episodic, cryptic, elegant, and sometimes as brief as tweets. But Pascal was one of the greatest mathematicians of all time and his defense of Christianity would help remind today’s students that having a mind and following Jesus is not a contradiction.

Not one book but the great tragedies of Shakespeare—the most profound and beautiful of literary works and abidingly contemporary.

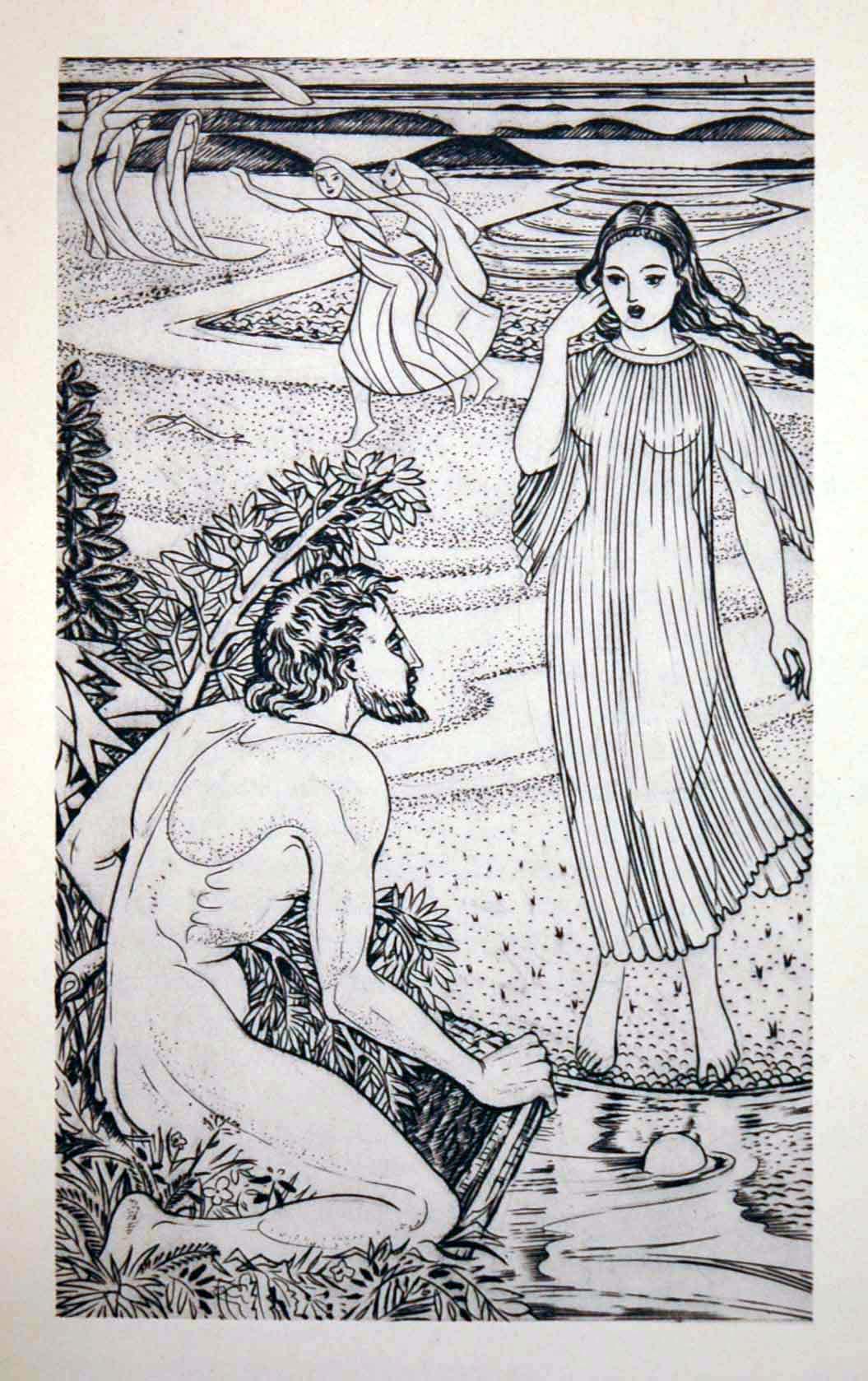

The Odyssey, Homer’s epic poem, written almost 3,000 years ago, was the beginning of, and has exercised an enormous influence on, all Western literature. For students today, it offers high drama, unforgettable characters, and easily recognizable, and very contemporary emotions, ambitions, and plot resolutions. I can think of no other single book from which one can learn as much.

Montaigne’s Essays. Why? Because they teach you how to learn, how to observe the peculiarities of life, how to be a good friend, how to know and be honest about yourself—and how to spend the last years of your life once you have done your part to make the world a slightly better place.

Every college student should read Randall Jarrell’s Pictures From an Institution, the funniest college novel ever. The book is written from the perspective of a highly disaffected instructor, and it’s an education in itself to see the world from the point of view of another person, merrily slicing away at that world with the glittering scalpel of his humor.

Hamlet. If you have never read—and grappled with—Hamlet, it is very difficult to understand modern culture: the intense sense of individuality and the fear that you are the pawn of political forces beyond your control; the feeling of empowerment and the intensity of despair; the wild blend of savage humor and melancholy.

Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Because it offers a panoramic view of Western Europe at a pivotal moment in its history—the Napoleonic wars; because it portrays the character changes of its entrancing protagonists—Pierre’s transformation from maverick playboy to soulful thinker, Natasha’s transfiguration from giddy debutante to dedicated earth mother—more vividly than any other novel I can think of; because its grandeur and vitality are such that even upon a fourth rereading I can’t put it down, and am at a loss to think of any fiction that would be tolerable in comparison.

Max Weber’s Economy and Society. In 1998, the International Sociological Association named Economy and Society the most important work of sociology of the 20th century. Now, there’s a piece of timid praise for you!—since with that book Weber supplanted Darwin as the greatest theorist of the modern age. Darwin’s theory of Evolution fit only dumb animals comfortably. When it comes to the creature who speaks—namely, man—we must look to Weber’s far grander theory of Status."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.